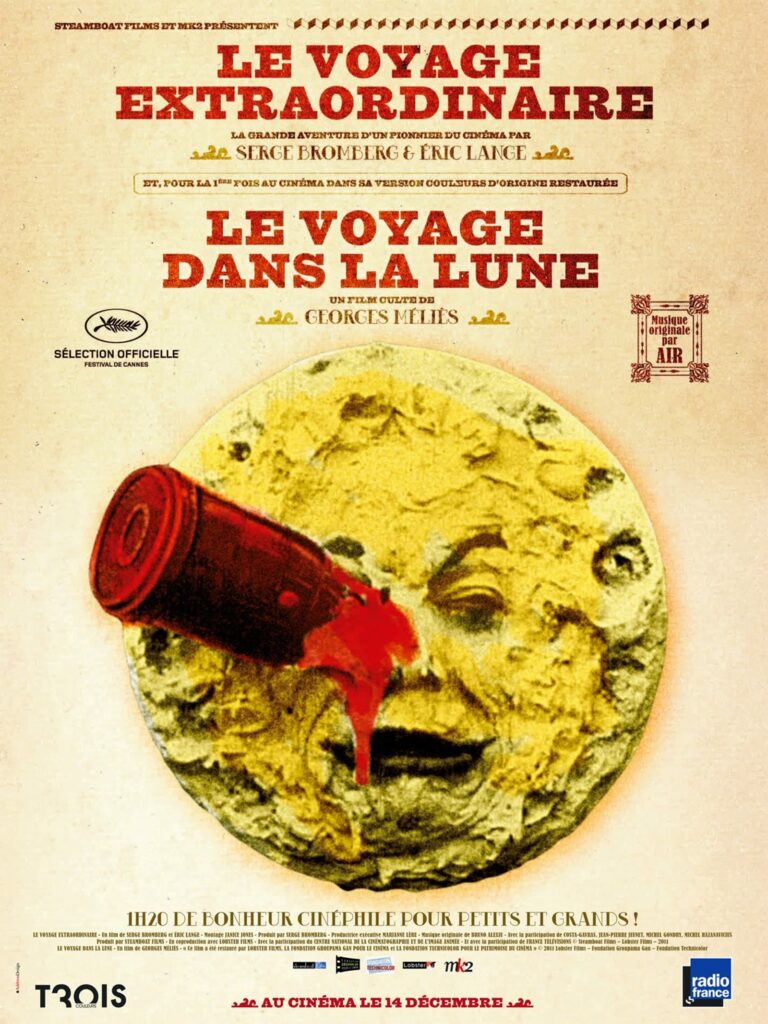

The first movie ever made was Le Voyage Dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon) by the French pioneer Georges Méliès in 1902. He had shot more than 100 short films to prepare himself for the 14-minute one-reeler and left audiences aghast with a rocket voyaging into space, circling planets and alien life forms that wouldn’t look out of place in a George Lucas film.

Georges Méliès had been inspired by his compatriots the Lumière Brothers. Auguste and Edouard after years working together created and screened the very first moving image in 1895. But where they had been content to record a train pulling into the station and workers flooding from factory gates, Méliès was a magician versed in the art of bringing rabbits from a hat and silk scarves from his sleeve. He realised that it was the manipulation of film that made it interesting and, with his theatrical ability to deceive the eye by skilful intercutting, he can safely be described as the Father of Film Editors.

The First Movie Ever Made in America

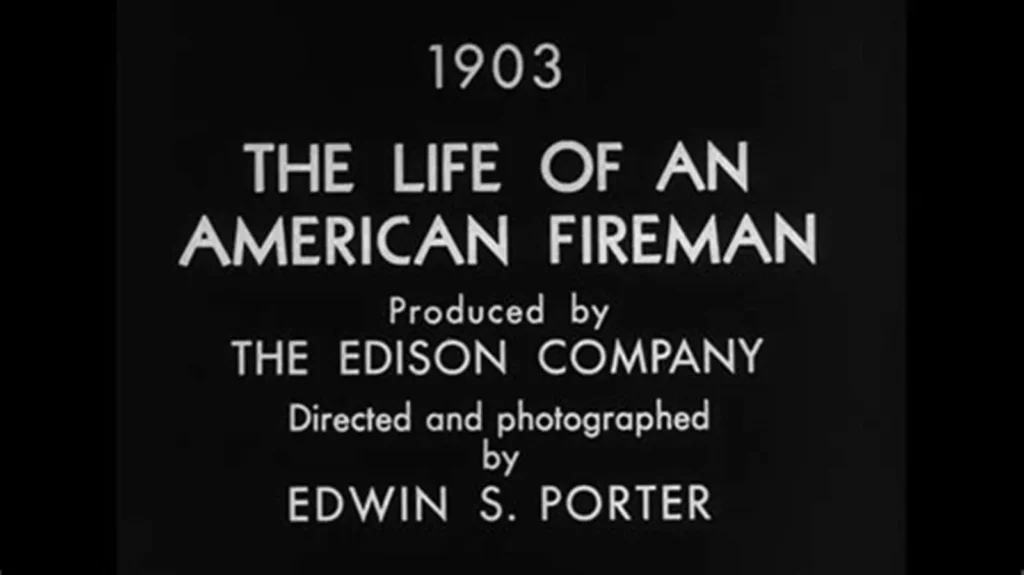

When the former camera operator Edwin Porter in 1903 was given the job on Thomas Edison’s New Jersey lot of directing a narrative documentary called The Life of the American Fireman, he made a study of Méliès’ work and realised that it was the Frenchman’s astute editing that made his films compelling. In his six-minute short, rather than merely filming firemen at work, Porter had them re-stage various activities. He used close-ups to show emotion and took the viewer into the heart of the drama by cross-cutting between the interior and exterior of a burning house.

What Porter brought back to the lot was so original, it took Edison months re-watching The Life of the American Fireman before he fully appreciated what the director had achieved. As many of the most inventive writers and artists discover, anything too novel, too ahead of its times, will be met by confusion, even anger. Hollywood moguls aren’t looking for the unique and innovative, they want to see a fresh spin on last year’s blockbuster.

Edison, though, was a shrewd entrepreneur, as well as a filmmaker, and later that same year put Porter back in the director’s chair to shoot a fictionalised account of a true story. Just as young American directors in the sixties analysed the work of the iconoclastic Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) aesthetics of François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Éric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette, Edwin Porter steeped himself in the work of filmmakers working across Europe before beginning to film his milestone movie The Great Train Robbery.

The Great Train Robbery

The 10-minute short was taken from a popular stage play loosely based on the real life heist by Butch Cassidy’s Hole in the Wall gang in 1900. Butch (George Leroy Parker) and the boys stopped a Union Pacific Railroad train in a sparsely populated stretch of wilderness outside Table Rock, Wyoming. They threw the fireman off the moving train, forced the conductor to uncouple the passenger cars and dynamited the safe in the mail wagon before escaping with $5,000 in cash.

Porter dressed locations in New Jersey to look like the Wild West and created the stock elements of the Western: the robbery, the shoot-out, the horseback chase, the gathering of the posse. Using both the newspaper transcripts and the structure from the stage play, Porter in 14 scenes created a vibrant narrative but, what made The Great Train Robbery so important, was Porter’s extension of film language.

It was the first movie ever made out of chronological sequence. Porter showed parallel-action between simultaneous events – intercutting, for example, between the bandits and the telegraph operator – and moved between scenes without using fades or dissolves. Another first was, having shown the fireman as he is about to be thrown off the train, Porter cuts back to a figure (a dummy) rolling in the dust.

One last Porter innovation was an added scene that could be placed either at the beginning or the end of the film (depending on the exhibitor) showing a bandit shooting his six-gun dead eye at the audience.

Adapted from Making Short Films: The Complete Guide from Script to Screen, Clifford Thurlow and Max Thurlow, Bloomsbury 3rd Ed.

To see more articles related to this topic, follow this link.